Many capable leaders serve on non-profit boards. They are aided by a voluminous literature and many training opportunities on effective governance, and by numerous efforts to define effective governance models, functions and frameworks. Yet, many sector leaders still struggle to fulfill the roles and responsibilities expected of them. Why this disconnection?

Peering into the Future, a new report from Mowat NFP’s Enabling Environment series, tackles this challenge and proposes a new approach to alleviating it. Here are the key takeaways from this report:

Governance is one of the most challenging and complex issues in the non-profit sector

Non-profit organizations differ in mission, size, and operating model. There is no prescriptive “one size fits all” model of governance. The legislative and regulatory requirements for non-profit governance vary across provinces. Different models of governance are therefore appropriate for different non-profit organizations in different jurisdictions.

An increasingly complex operational environment is driving tensions within organizations that can be difficult to reconcile

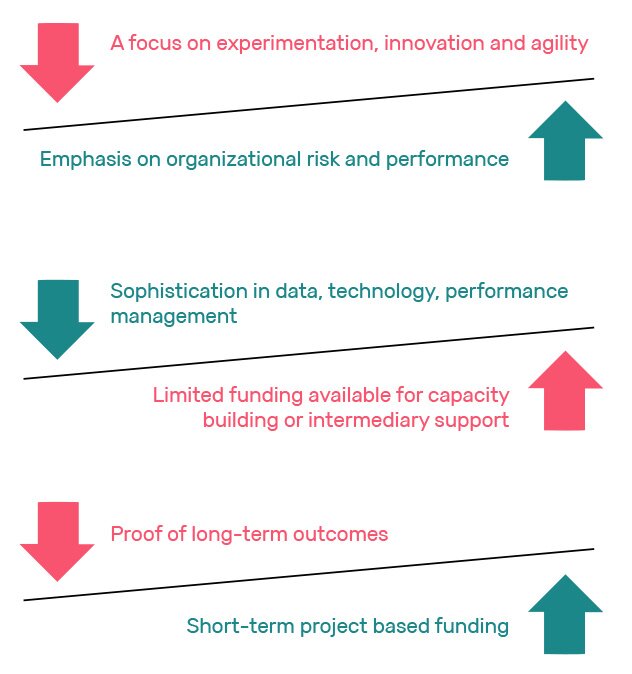

Factors contributing to this complexity include:

- A growing demand for services from increasingly diverse communities.

- Increasing demands from governments and funders.

- Greater focus on collaboration, mergers, network-based models of organizing, cross-sectoral partnerships and common approaches to measuring impact in the sector.

- Technological changes, volunteering trends, and a new generation of leaders are changing how non-profits work and how they interact with and engage one another, funders and the public.

Boards are struggling to adjust to the changing environment and face capacity and recruitment challenges.

Organizational Tensions

There is much at stake when governance is ineffective

Resources may be misused or misdirected, an organization may lose its strategic direction, its reputation may be weakened, poor working conditions for staff could arise, and members of the board could incur personal and professional liability. Ultimately, ineffective governance compromises an organization’s ability to meet the needs of its beneficiaries and key stakeholders.

Boards have taken on the primary role in governance, but that is actually not something that is required by regulation

Governance is typically regarded as something boards do, but this does not mean that the board should be the only mechanism of non-profit governance. Rather, governance is a series of functions that must be fulfilled, and the board is one structure to assist in that process. The way the governance body is structured is largely at the discretion of the organization.

The functions boards fulfill have grown over time, but it is wrong to see many of these additional functions as governance ones

Governance involves a core set of requirements: oversee performance and evaluation, ensure financial stability, execute fiduciary duties, and ensure compliance and accountability. Boards are now expected to fulfill a much wider variety of functions, but many of these should not be considered governance ones:

Board Functions

This complex reality places new demands on board members that many boards find difficult to meet

Non-profit boards now are expected to work across sectors and systems. They need to be data experts, strategists, sense-makers and innovators. They must also be financially literate (including in emerging areas, such as social finance and earned income) and willing to take calculated risks, while being inclusive, resilient, trustworthy and self-aware. Many boards are struggling to adjust to the changing environment. While there are successful examples of board governance in Canada, many organizations struggle with leadership and management issues. Many boards remain underutilized, ineffective, dysfunctional or overburdened with operational issues.

In this reality, the board can no longer be seen as the sole locus of governance

Governance needs to be approached in a new, transformative and adaptive way. Governance must be envisioned as collaborative – a function that is shared and not limited to the board. This is essential to ensuring better responsiveness to social issues, system-wide impact and adaptability to the changing environment.

How can this new vision be achieved?

The voluminous literature offers no transformative silver bullet to achieve this vision. But there are a number of promising practices that, taken together and bolstered by new practical approaches, can achieve the needed transformational change. This approach may mean harder work and a longer road, but the transformation the sector needs has no identifiable shortcuts. Some starting points elaborated in the paper include:

- Sharing power rather than centering it solely with a board or management team

- Separating fundraising from the board

- Leveraging new technologies to create more meaningful and direct engagement with beneficiaries and stakeholders

What are some of the obstacles to overcome?

Philosophical differences can influence choices around governance practices. Governance may also be influenced by board members’ understanding of impact. Cultural barriers are built into some current governance practices. Volunteer board members face similar expectations and even the same liability requirements as for-profit board directors. These are all contentious issues that sector leaders must consider on the road to transforming organizational governance in the sector. As a result, agreement on a principles-first approach may be challenging to achieve, so learning by doing is likely the more fruitful approach.

The way forward: explore, convene, test and iterate, promote, and connect to other policy initiatives

Improving the sector’s capacity for “future-oriented” governance will require a combination of steps. Key among them:

- Promote and incentivize the exploration of governance approaches that are impact driven, rather than siloed and organization-specific.

- Convene to reflect on governance opportunities, challenges, and solutions.

- Test and iterate new governance models and approaches.

- Promote governance through mentorship, leadership training and skills development.

- Connect governance initiatives with upcoming policy initiatives.

Author

Lisa Lalande

Release Date

September 27, 2018